Production

Development

Lee Unkrich first pitched an idea for the film in 2010, when Toy Story 3, which he also directed, was released. Initially the film was to be about an American child, learning about his Mexican heritage, while dealing with the death of his mother. Eventually, the team decided that this was the wrong approach and reformed the film to focus on a Mexican child instead. Of the original version, Unkrich noted that it "reflected the fact that none of us at the time were from Mexico." The fact that the film depicted "a real culture" caused anxiety for Unkrich, who "felt an enormous responsibility on [his] shoulders to do it right."

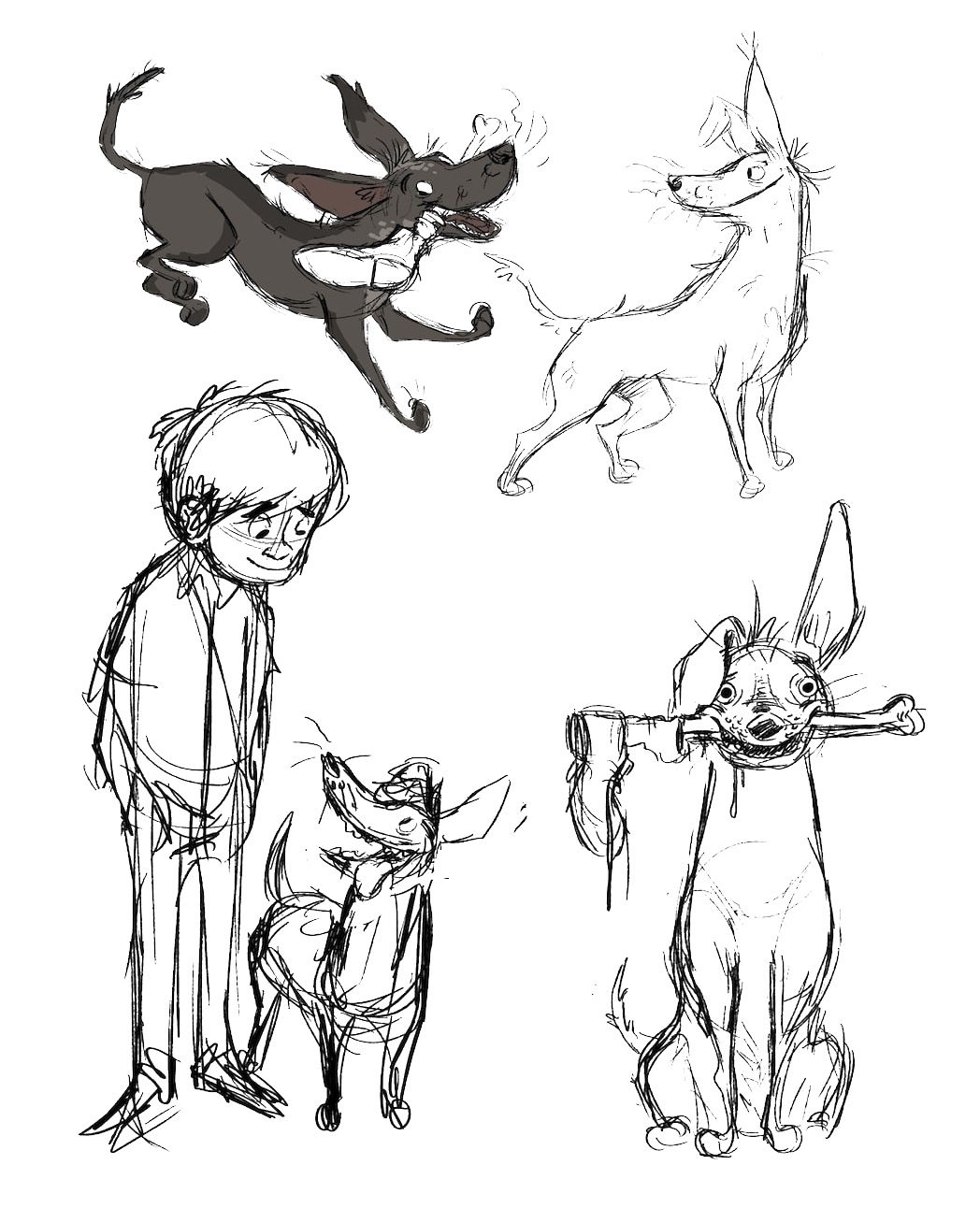

The Pixar team made several trips to Mexico to help define the characters and story of Coco. Unkrich said, "I'd seen it portrayed in folk art. It was something about the juxtaposition of skeletons with bright, festive colors that captured my imagination. It has led me down a winding path of discovery. And the more I learn about [el] Día de los Muertos, the more it affects me deeply." The team found it difficult working with skeletal creatures, as they lacked any muscular system, and as such had to be animated differently from their human counterparts. Coco also took inspiration from Hayao Miyazaki's anime films Spirited Away (2001) and Howl's Moving Castle (2004) as well as the action film John Wick (2014).

In 2013, Disney made a request to trademark the phrase "Día de los Muertos" for merchandising applications. This was met with criticism from the Mexican American community in the United States. Lalo Alcaraz, a Mexican-American cartoonist, drew a film poster titled Muerto Mouse, depicting a skeletal Godzilla-sized Mickey Mouse with the byline "It's coming to trademark your cultura." More than 21,000 people signed a petition on Change.org stating that the trademark was "cultural appropriation and exploitation at its worst". A week later, Disney canceled the attempt, with the official statement saying that the "trademark filing was intended to protect any title for our film and related activities. It has since been determined that the title of the film will change, and therefore we are withdrawing our trademark filing." In 2015, Pixar hired Alcaraz to consult on the film, joining playwright Octavio Solis and former CEO of the Mexican Heritage Corp. Marcela Davison Aviles, to form a cultural consultant group.

Lee Unrich

director and writer

Hayao Miyazaki Anime

An important source of inspiration for the film

Story

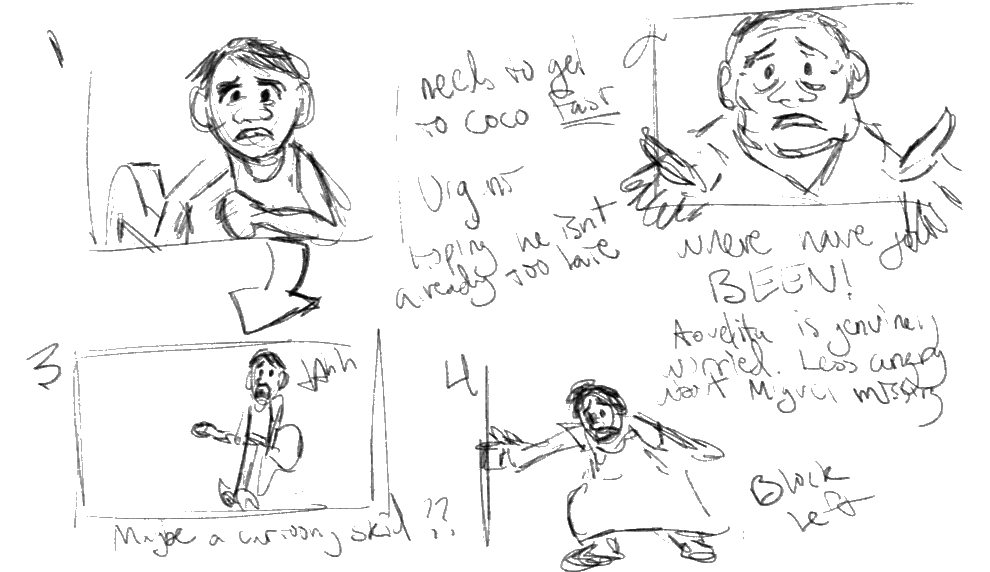

Unkrich found writing the script "the toughest nut to crack". Earlier versions of the film had different universe rules regarding how Miguel (originally called Marco) would get back from the land of the dead; in one case he physically had to run across the bridge. In one version of the story, his family is cursed with singing when trying to speak, which was included as a technique to add music to a story where music is banned.

Music & Soundtrack

The film's score was composed by Michael Giacchino. Germaine Franco, Adrian Molina, Robert Lopez, and Kristen Anderson-Lopez wrote the songs. Recording for the score began on August 14, 2017. The score was released on November 10, 2017.

Originally, the film was meant to be a "break-into-song" musical. Lopez and Anderson-Lopez had written many more songs for the film than what ended up in the released version; one piece that survived in storyboard until late into the production was an expository song that explained the Mexican holiday to viewers to begin the film. In another song, Miguel's mother explains the tradition of shoe-making in their family, and how this means he is not allowed to pursue music. Plans for the film to be a full musical film were scrapped following early test screenings.

Following the 90th Academy Awards ceremony, where "Remember Me" won the award for Best Original Song, the album broke the top 40 on the Billboard 200 charts, jumping from 120 to 39, where it peaked before dropping to 64. In the week of March 8, the Miguel version of "Remember Me" gained 1.58 million plays via online streaming, according to the Nielsen Music.

Remember Me

This iconic song is written by Robert Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez. The song is performed variously within the film by Benjamin Bratt, Gael García Bernal, Anthony Gonzalez, and Ana Ofelia Murguía. Miguel and Natalia Lafourcade perform a pop version of the song that is featured in the film's end credits. Carlos Rivera recorded a cover version of the song, titled "Recuérdame" for the film's Spanish-language soundtrack album. It won Best Original Song at the 90th Academy Awards in 2018.

Listen here!First Four Tracks

Remember Me

Benjamin Bratt

Much Needed Advice

Benjamin Bratt and Antonio Sol

Everyone Knows Juanita

Gael García Bernal

Un Poco Loco

Gael García Bernal and Anthony Gonzalez

Casting

Coco is the first-ever motion picture with a nine-figure budget to feature an all-Latino cast, with a cost of $175–200 million. Gonzalez first auditioned for the role of Miguel when he was nine, and was finalized in the role two years later. Speaking of his character, Gonzalez said: "[Miguel and I] both know the importance of following our dream and we know the importance of following our tradition, so that's something that I connected with Miguel a lot". During the film's pre-production, Miguel was originally set to be voiced by a child named Emilio Fuentes, who was removed from the role after his voice deepened due to puberty over the course of the film's production.

In 2016, the Coco team made an official announcement about the cast, which revealed that Gael Garcia Bernal, Benjamin Bratt, Renée Victor, and Anthony Gonzalez would voice the characters. Bratt, who voiced De la Cruz, was "moved" when he realized that Disney-Pixar wanted to make a film on Latin culture. Disney officials closely monitored Bernal's movements and expressions while he voiced the characters and used their input for animating Héctor.

Bratt voiced Ernesto De la Cruz, a character who he described as "the Mexican Frank Sinatra"; "[a] larger than life persona". On the advice of the filmmakers, Bratt watched videos of equivalent Mexican actors including Jorge Negrete and Pedro Infante. Bratt found the character similar to his father in physical appearance, "swagger and confidence", and worked in the film as a tribute to him.

The character Mama Imelda's voice was provided by Alanna Ubach. Ubach felt that the film "is [giving] respect to one quality that all Latin families across the universe do have in common, and that is giving respect and prioritizing the importance of family". Mama Imelda's voice was influenced by Ubach's tía Flora, who was a "profound influence in [her] life". Ubach felt her tía was the family's matriarch, and dedicated the film to her tía.

Unkrich stated that it was a struggle to find a role in the film for John Ratzenberger, who is not Latino but has voiced a character in every Pixar film. As Unkrich did not want to break Pixar's tradition, Ratzenberger was given a minor role with one word making it Ratzenberger's shortest Pixar role.

Animation

On April 13, 2016, Unkrich announced that they had begun work on the animation.[43] The film's writer, Adrian Molina, was promoted to co-director in late 2016.[14] Unkrich said that Pixar wanted "to have as much contrast between" the Land of the Living and the Land of the Dead, and that many techniques were used to differentiate the worlds. Color was one: "Given the holiday and the iconography, [Pixar] knew the Land of the Dead had to be a visually vibrant and colorful place, so [they] deliberately designed Santa Cecilia to be more muted" said Unkrich.[3]

According to Harley Jessup, the film's production designer, Santa Cecilia is based on real Mexican villages, as the production team "stayed grounded in reality in the Land of the Living". Chris Bernardi, the film's set supervisor, said that the town was made small so Miguel could feel confined. Bert Berry, the film's art director, said that aged building materials were used in order to depict Santa Cecilia "as an older charming city".[3] According to Unkrich, Miguel's guitar playing is authentic, as they "videotaped musicians playing each song or melody and strapped GoPros on their guitars" to use as a reference. For the scene in which Miguel plays music in his secret hideout, the filmmakers used "very elegant, lyrical camera moves" and "gentle drifts and slow arcing moves around Miguel as he plays his guitar with very shallow depth of field to enhance the beauty of the soft-focus foreground candles".[3]

For the Land of the Dead, Unkrich did not want "to have just a free-for-all, wacky world", wanting instead to add logic and be "ever-expanding because new residents would arrive regularly". Jessup said that the animation team wanted the Land of the Dead "to be a vibrant explosion of color" when Miguel arrives. Jessup also said that "Lee [Unkrich] described a vertical world of towers, contrasting with the flatness of Santa Cecilia. The lights and reflections are dazzling and there's a crazy transportation system that connects it all. The costume colors are much more vibrant than in the Land of the Living, where [the animation team] tried to stay grounded in reality. [They] really went all out in the Land of the Dead to make it a reflection of the holiday". According to David Ryu, the film's supervising technical director, the animation team "figured out a way to introduce a single light — but give it a million points" for the scenes on the outside in the Land of the Dead: "The renderer sees it as one light, but we see a million lights".[3]

According to art director Daniel Arraiga, the animators "had to figure out how to give [the skeletons] personality without skin, muscles, noses or even lips" and that they "played with shapes and did a lot of paintings. [They] sculpted and studied skulls from every angle to figure out where [they] could add appeal and charm". Global technology supervisor J.D. Northrup was hired early in the film's production in order to avoid potential issues in the film's animation process. Northrup said that "Each [of the skeletons' pieces] had to be independent so the complexity of the rig and the stress that it puts on the pipeline were something like we've never seen before." Northrup was also tasked with simplifying the skeleton's elements to render the skeleton crowds. In order to create the skeletons, several additional controls were used, as they "needed to move in ways that humans don't," according to character modeling and articulation lead Michael Honse. Honse said that the bones were a particular problem, stating that "there was a lot of back-and-forth with animation to get it right," but found "really cool ways" to move the skeletons.[3]